Article by Claudia Spaziani Testa

“The future of design is a future where anything material in the environment — whether it’s wearables, cars, buildings — can be designed with this variation of properties and relationship with the environment that can take part in the natural ecology. Hopefully, it points towards a shift that goes beyond the age of assembly into the age of a new kind of organism.”

Have you ever wondered what it means to be a genius? Why are Michelangelo and Leonardo so extraordinary? I would answer that, with their exceptional intelligence, they were able to combine anatomy and frescoes (Sistine Chapel), engineering and drawings (Leonardo’s machines), art and science to imagine a new world starting from reality. Every age has its geniuses, individuals that are always questioning the world around them, who are able to think outside the box and surprise everybody with their extraordinary inventions. One of ours is Neri Oxman, an architect, designer, and professor at MIT.

Daughter of two architects, Neri was born in 1976 and raised in Haifa, Israel, a town located between hills and the sea, where connection with nature feels stronger. When she was a child, she was fascinated by her surroundings and spent hours and hours in her grandmother’s garden, a magical place with a huge variety of plants on the top of Mount Carmel. She has always been a curious person, always trying to understand the world around her in a scientific way: before beginning Architecture studies, she had attended Medical school for two years.She also served in the Israeli Air Force, managing to become first lieutenant: perhaps this experience has contributed in making her such a bold thinker.

In 2010, Oxman became a professor at MIT Media Lab, where, for nearly a decade, she led the Mediated Matter Group. MIT Media Lab is a research laboratory founded in 1985 in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with the mission to invent transformative technologies, experiences and systems that enable people to reshape their lives. They have access to the most sophisticated technologies on the planet & their designs aim at the future/at solving future issues: ‘if something can be useful in the present, it’s already too late’, they say.

In order to explain how Neri works we can look at her project The Krebs Cycle of Creativity, completed in 2017, which highlights how art, science, engineering and design are not separated fields of knowledge but part of the same creative process: in her creations, she combines computational design, additive manufacturing, materials engineering and synthetic biology.

When she was working in the Lab, she told her team members: ‘You have to be ready for your project to appear in the atrium of the MoMA and at the same time on the cover of Nature and Science. We don’t do either, it’s always both’.

It is no coincidence that Oxman’s works are often displayed in permanent collections at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, the Smithsonian Institution, the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna (MAK), the FRAC Collection and the Boston Museum of Science and in other prestigious private collections.

One of her most famous works is the Silk Pavilion, 2013. It is an enormous dome created with a mixed technique of biology and robotics: in three weeks a robotic arm and 6500 living silkworms built the structure, and each insect spun a single thread filament that is about 1 km long. This is a great example of collaboration between humans and other species in order to craft new materials and structures that don’t deplete natural resources.

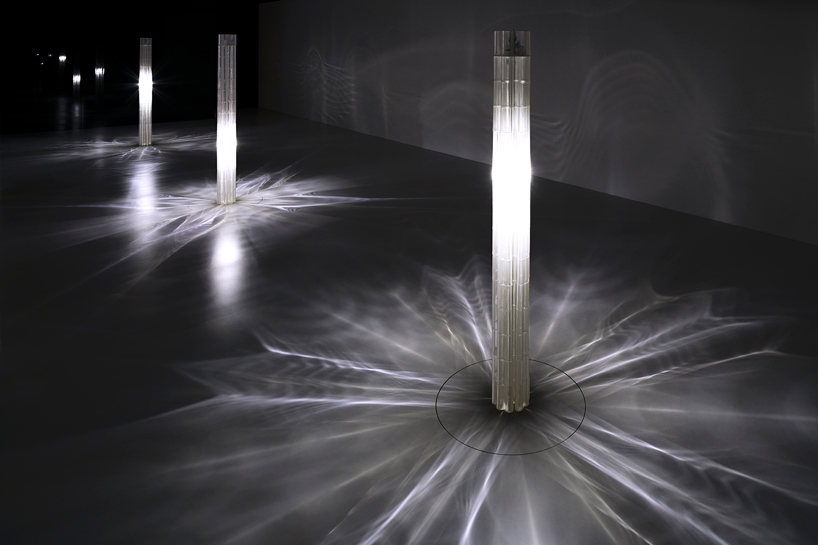

In 2017 the group presented an installation for Milan Design Week. It was a series of 3-meter-tall glass columns fully manufactured with the Glass 2 platform. Each column was unique, the result of the use of G3DP2, a large-scale, additive manufacturing technology for 3D printing, that is able to predict mechanical and optical properties of the material.

The project Aguahoja I (2018-2022) is a 5-meter-tall architectural pavilion composed of the most abundant biopolymers on our planet as cellulose, chitin and pectin – materials that can be found in apple skin, trees, and crustaceans. It provides a material substitute for plastic, breaking the harmful waste cycle through the creation of biopolymer composites: these renewable and biocompatible polymers leverage the power of natural resource cycles and can be engineered to decompose as they return to the earth, contributing to new growth and reflecting the ancient biblical verse ‘from Dust to Dust’. In addition, the process of creation of Aguahoja I involved the development of a robotic platform for 3D printer materials.

First of all, Neri Oxman reminds us of how important it is to ask ourselves deep questions about our reality. She teaches us to be bold in thinking and creative and innovative even in the way we ask questions, not abiding by rules and schemes but rather preserving a child’s spontaneity.

Then, Neri teaches us to seek answers in a profound manner, combining skills borrowed from various fields of knowledge. Only by combining seemingly different things like art and science can we reach the truth.

Finally, her work is concrete proof of how art and design are only meaningful if they serve humanity and the only way to go is discovering new solutions to protect the natural environment, as she does every day.

Bibliography:

https://oxman.com/projects

https://www.media.mit.edu/

https://www.media.mit.edu/groups/mediated-matter/overview/

https://www.netflix.com/it/title/80057883

https://www.ted.com/talks/neri_oxman_design_at_the_intersection_of_technology_and_biology

Leave a comment